Despite working in some of the most dangerous places in the world, West Dorset photographer Carlos Guarita reflects on his life’s work with good humour.

Insisting he is not a war photographer, Carlos has nonetheless spent much of his working life in African combat zones, often behind the frontlines capturing a first-hand view of how people are affected by brutal regional conflicts and civil wars.

Having discovered an appreciation for the work of photojournalists such as Don McCullin as a teenager, Carlos got an early break as a photographer when he was commissioned to take shots in a Scottish prison on behalf of the Prison Reform Trust.

Some of Carlos’s photos were picked up by The Observer, helping launch a career that saw him go on to cover the human cost of conflicts in places such as Angola and Mozambique.

“War photography at that time in the early 1980s was all about showing the effect of these conflicts but not understanding what was going on behind it,” said Carlos.

“Photography is often about conflict, and about war to some extent, but not all of it and I wanted to show a different side to things.

“I’ve worked in combat zones closely with armies, but I’m not a war photographer.”

Having co-founded the Reportage photo agency and a photography centre in Nicargua, Carlos went on to photograph young militia men conducting rifle training drills with wooden sticks in Inhambane, Mozambique in 1984.

The militia were training to defend against attacks by the Mozambican National Resistance known as RENAMO (Resistência Nacional Moçambicana).

In Mugulama, central Mozambique, in 1990, Carlos photographed refugees left starving and exhausted behind RENAMO rebel lines. These people were later rescued by Liberation Front of Mozambique (FRELIMO) government troops.

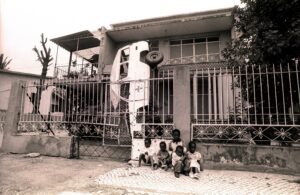

In central Angola in 1993, Carlos photographed the aftermath of aerial bombing by People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) government planes against the town of Huambo while it was under the control of the rebel UNITA party.

Many of these photos were published by national newspapers and magazines overseas.

Carlos said: “When you see people living in just terrible conditions in refugee camps and out on the streets, I felt I wanted to look into the causes of this misery.”

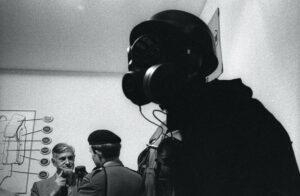

Going behind the scenes of ‘the misery’, Carlos also began photographing UK military fairs and weapons conventions in the period before the first Iraq war.

Often overlooked by mainstream media at the time, Carlos found these events ‘where people make astonishing amounts of money’ fascinating.

At a military fare in Aldershot in 1988, Carlos photographed military officials from Saudi Arabia, Spain and Chile watching what was described as a ‘pyrotechnics’ display. Carlos also photographed a potential customer trying out a LAW 80 light anti-tank weapon for size. Newer versions of this weapon have been supplied to Ukraine to help fight the Russian invasion.

“I realised quite early on I didn’t want to be war a photographer,” Carlos said.

“I had a friend who was killed in an airstrike when he was embedded with a group of Kurds.

“The most dangerous thing I ever did was cross a minefield, but that was along a path that had already been marked and I was with a demolition guy and a sniffer dog.”

Now aged 76, Carlos has been retired for 11 years. Looking at the photojournalism industry now, Carlos says it has been majorly affected by two factors: digital photography and 9/11.

“Editors now want live video rather than artful black and white photos,” said Carlos. “Early on in my career I very often would have to pay my costs to cover a job and then make sure I made my money back afterwards in sales, but I think I got away with that by having a bit of a sense of humour.”